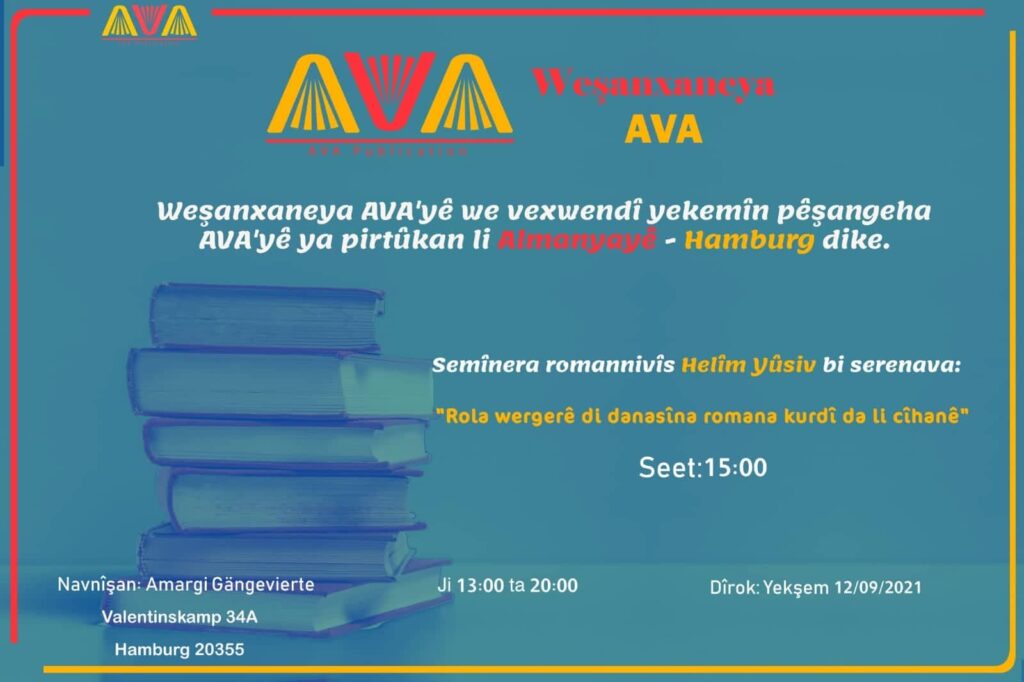

ESSAY: A kid’s history and two languages – a memoir by Halim Youssef

Transcript Ausgabe 36. 10.Januar 2011

Editorial

The literatures of stateless nations

A kid’s history and two languages, a memoir by Halim Youssef

translated from Kurdish into English by Khadija Baker

The first language is the mother tongue, the language of your home, the language of your brothers and sisters and the language of your neighbours. The second language is the language of the teachers, police, state officials, intellectuals and the holy books.

It might be destiny that led both languages to confrontation and war. In this war one of these languages had to perish and die, while the other language had to live and thrive. One turned into a fatal language, while the other licked its wounds, drowned in its blood, and died in silence.

* * *

When I came to this world, it was my fate to be lulled in the cradle in my mother tongue.

This language was drowning in its wounds, but resisted death. And we, the children of that wounded language, we hurried, even so late, to rescue it from extinction.

Here I am reading to you in that language the story of life and death. This story is about the spirit of a people who found themselves suddenly surrounded by betrayal.

Under the siege of blind history, and stabbed by the knife of a tousled-hair geography, and scattered in between the dogteeth of four savage countries.

* * *

This sad story always sets its traps in childhood. This story, which begins by cutting off the stunned child’s tongue, and planting another one into his mouth. It goes further, putting another brain in his head, and another spirit in his body.

The child I spoke to you about is now a writer without a country, a bird without wings, and a man who does not find a foothold for his wandering foot. That child is the same child that all countries and their troops came together to extract his tongue from his mouth and simply make him dumb.

Quite simply… This child is me.

[…] And the mother tongue is a plant, a beautiful one, and the gift of God can not be returned.

* * *

At that time he turned six. It was his first time out of his house, standing face to face with that huge and strong wall named language. His father was holding his hand and led him, accompanied by his elder brother, who was going to translate for him. They went to knock on the door of the castle called school, the castle of the other language. His father wanted to register him at school; the child was busy watching the official, an elegant one, speaking in a language he couldn’t understand. The child’s brother was speaking the same language with the official. They were mentioning his name and talking about things that a child could not comprehend.

His head flooded with an intense fog.

Then something small burned in his heart, and then it smelled of some death. He sensed empathy and sorrow in his spirit, and heard the song of a bird that has been killed. Voices turned into smoke rising into the sky. That child who has just turned six, and sunk into astonishment … it was me; and that city was Amoude… That unforgettable smell was the aroma emanating from the ban imposed on my mother tongue.

Maybe that dead bird was … my heart.

* * *

The first language is the language of the soul – the language of feelings, the language of a beautiful woman and the language of wonder…

The second language is the language of schools and universities, the language of intellectual and consciousness, and the beautiful language of the state.

* * *

That child grew up, went to schools and universities. In that beautiful language of the state he wrote in newspapers, magazines and books. He got older, and grayness invaded the hair of his entire soul. To calm down the snaps of fire in his burning soul he stained the faces of white papers with his black ink. He wrote stories about forbidden language, forbidden love, and forbidden life. A black ink inspired in its darkness by the darkness of night. He wrote at night and slept during the day. He did not need daylight. The fires of his soul were enough to brighten his nights. Until one winter’s night when he lay on the ground reading. His mother came and stood over his head and asked: ‘What are you writing, my son?’

Suddenly he felt that, if he read all that he had written she would not understand a single word. This was the second time that he sunk into surprise and astonishment. Broken, he stared into his mother’s eyes and felt ashamed of himself.

By the time he turned thirty he knew that he had the wrong key in his hand, a key which wouldn’t open the closed door of his soul. He discovered that he had lost the right key when he was six years old.

* * *

The next day, as a child who had lost his mother when he was six years old, that sad man came back into her arms and found her again. He received the key of life from her hands and kissed them. From one eye he cried tears of subjugation …, and from the other eye tears of joy. His long crying and loud giggling turned into letters, words, and then to stories and novels. That broken man who still writes with spirit of a six-year-old child… is me.

* * *

Tomorrow, in the same country and in the same city, which I descended from, another child will turn six years old. His family will register him in the same school and he will leave his wonderful language at home. He will be shocked by the language of his teachers. He will grow up in a fog of astonishment and amazement. What I fear is that a Kurdish man will stand before you after another forty years have passed, and will tell to you exactly what I am telling you now. He will tell you about the horror of killing a human being called the mother tongue.

PROSE: When Fish Get Thirsty by Helim Yusiv

When Fish Get Thirsty

Translated from the Midja Ahmad & Serkewt Karimi

Confessions of the steel door

I’m the steel door in Fish’s room. Our acquaintance goes back to the time when he wanted to get settled in this town. I was just one of many doors in the shop when he bargained with my owner. The thing that struck me was that a young man that had just arrived was bargaining for doors and wanted to build a home. We were used to big buyers but this time we had a small customer. Even though he had another man with him, he was the one doing the bargaining. In the same way I noticed him it was obvious that he also noticed me. He turned to me and put his hand on my chest.

– This is the door I’m looking for.

He and my owner made a deal. When he brought me here everything was ready. He easily put me in my place and I have been protecting his home ever since. Sometimes he and Bozo stay inside together. Sometimes Bozo stays in his house next to me. But most of the times when he goes out by his self he lives Bozo inside. But of course after the incident with the dog massacre when Mahsum hunted dogs like a wild enemy, Bozo was stuck staring at me for nearly two months. Fish would close me on him and bring him everything he needed until there no longer was danger and everything returned to normal. During those days Fish used to sit by himself for hours. He would put his head between his hands and mumble. Like a person who had lost something he would sit and stare at the wall for hours. Every now and again he would change the wall he was staring at and sit quietly. Oh how I wished that I had a voice so I could ask what it was he was looking for, but in the end I was only a piece of rusted metal who nobody really paid attention to. I had no idea what he was doing outside. One day when Fish came home we was carrying a small rug and a thick book, it wasn’t until later that I realized that is was a holy Koran. He replaced the staring at the walls with prayer and reading the Koran. In the beginning he was quiet but then he started reading the Koran with a pleasant and clear voice. I could not understand what he was reading yet I wanted him to read the Koran to me in his delightful voice. He had made some shelves in the room which he had filled with thick books. All the books were about the clarification of the Koran, the life of the prophets and all the good men of God. Like a cat looking for a hidden mouse Fish was looking for things in these books. He wanted to get well and be released form his confusion and restlessness. He used to tell Bozo about his visits to the mosque. He was happily anticipating the arrival of a great Sheikh. The night before the arrival the excitement kept him from getting any sleep, and I just listened to him. He left early in the morning. Hundreds of spiritual leaders and supporters were awaiting the white car in which the Sheikh dressed in white was riding. Some were awaiting the Sheikh in their own white cars in the outskirts of town; others filled the streets around the mosque. Some spiritual leaders nearly lost their minds from all the excitement. One of these caught Fish’s attention more than the others. He was in a trance with his long white beard waving with the motion of his head. His turban had fallen to his feet and with a barking sound he repeated, ‘I am the loyal dog of my Sheikh.’ At the same time Fish could not help of thinking about Bozo and asked himself:

– How would Bozo act if he was in a trance?

With the arrival of the Sheikh at the mosque door, some started screaming while others were lining up people on two sides. The white dressed and well-smelling Sheikh spread his arms like wings as he was walking slowly through the crowds; everyone was fighting for a chance to kiss his hand or even to touch him. One of the people that got a chance to kiss the Sheikh’s hand was Fish. This kiss left him in a state of confusion for several days:

– They said he smelled of musk and flowers , but I did not believe them.

He brought his hand close to Bozo’s nose.

– Smell it Bozo, it smells of paradise.

With the arrival of the Sheikh the mullas gathered all the ones that had the need to confess and ask for absolution. They would put them in groups of six to seven people and hand the group over to one of the mullas. The mulla would talk about the process of forgiveness: the confessor has to go to the Sheikh and then not speak to anyone until the next day. They have to wash themselves, pray and read the Koran and stories about the prophets. The confessor has to remember one hundred deceased and also bear in mind that he will also one day face the judgment of his God. That evening Fish came home a forgiven man. He was happy: he would no longer be a man with sins; by the morning all his sins would be washed away. When he got home he washed himself right away and started to read the Koran. He stayed up half the night praying, and remained quiet until Morning Prayer. After the sun came up he started talking and happily prepared food for himself and Bozo. During those days the old man married to the old lady next door passed away. The old lady had asked Fish to say some prayers for the dead old man. Even though his relationship with the old lady was not wholehearted he still went to her house as a good deed. From the day he got to know the old man, his shaking head had made him curious. His head would shake from left to right all day long, Fish used to tell Bozo long stories about it. As much as the old lady used to fuss around, the old man would stay silent. He used to take his little chair and place it in a corner of the room, put the Koran on its little chair and read it as his head kept shaking from side to side. Meanwhile the old lady was busy taking care of herself and her ill daughter Jamila. Jamila was the kind of girl everyone admired. Her beauty set an example for the rest of the girls. In those neighbourhoods the old lady had spoken of her daughter and said:

– God created Jamila for himself but accidently send her to earth.

Some people would speak among themselves and say that it is unbelievable that Jamila is the daughter of the shaking old man. She should have been the daughter of a beautiful man or the one of a ghost. Suddenly Jamila became confused and everyone said:

– Jamila has lost her mind; she is possessed.

Even so, people would come and ask for her hand in marriage; they hoped that marriage would bring her senses back and make her well again. However they tried, though, Jamila would not settle – she was in love with a young man. Later when they found the pictures of the young man hidden with Jamila they understood what the problem was. By that time the young man had got married and moved to another town, but he was still protected in Jamila’s heart. When a new marriage proposal was made the old lady decided:

– Jamila has to marry this man.

Jamila’s suitor was not only from a wealthy, well-known family, but also determined that he would not marry any other than the most beautiful woman in this country. They forced Jamila into the room with the mullah. The old lady fooled and scammed her into the marriage, and without a wedding her husband took her away. The first night she attacked him, hit him and said:

– I don’t love you.

Her parents-in-law and brother-in-law all had to help the groom to escape from her grip. A couple of days later Jamila had calmed down and was acting as a housewife. She swore that she did not attack him on purpose – the evil spirits did that, they had forced her to hit him. Her husband, just like her mother, kept on pushing spells on her and taking her to sheiks and exorcists. Everything went well until Jamila got pregnant and her due date came around. In the final hard hours of giving birth Jamila once again lost control and like a wild animal she attacked the doctors and nurses and destroyed everything in the hospital. More than eight people had to gather around her until her baby was born. After Jamila’s homecoming she went through yet another change. She confessed her deepest wish: her wish was that the father of her children would be her loved one that was the man in the picture. Once she told Fish that her brain was locked from all the beatings she had been given. When they found out that she was secretly visiting her lover, her mother had complained about her to her uncles. All of them had gathered around her and she had got confused from the pain and the fear of their beatings:

– Our honour is more important than our life. This time it is a beating, because nothing serious has happened, but next time it will be killing.)

Jamila had thrown all the talismans that were supposed to keep her from harm on the ground and had cried. Fish took her four talismans and hung them on his walls. After the confessions, Jamila started losing more and more weight for each day and slowly her beauty and the sparkle in her eyes was lost with it. If someone were to see her now they would never believe that once upon a time she was known as the most beautiful woman of this country. Jamila, just like thousands of others in this country, was struck by deafness and loss of speech, but even so the old lady would not stop fussing around Fish. On the day that the old man died the old lady had not allowed Bozo to come into the house, so Fish had returned early. When she saw Bozo she quickly ran to the door and begged Fish to leave him outside, she was afraid that he would make her house filthy. Fish wanted to leave as well, but since the old man was still on the floor, he left Bozo outside waiting for him and came back quickly then they both returned home with broken hearts. That night Fish wasn’t himself. He was staring at the wall and repeating:

– I will find it.

I didn’t understand what he was looking for or what he had lost, but it was clear that something huge was going on inside of him. His eyes were widened and he had started smoking. He had left the room in a big cloud of smoke and as if in a empty steel box his voice echoed back:

– I will find it.

Day by day the rows of thick books by the wall got higher and longer. Like a man in a bottomless sea Fish was swimming between the thick books. I never knew what it was he was looking for. He was looking for his mother, father, sister, brother or perhaps something unknown. He started in the afternoons and kept reading his books till morning, and when everyone else woke up he would fall in to a deep sleep. The next day he would continue, but the goal was the same:

– I will find it.